On 16 December 1944, the Germans launched Operation Watch on the Rhein, their last major counteroffensive on the Western Front. With the Red Army closing in from the East and the Western Allies on the German border, the German Army launched a desperate attempt to remove the American and British forces from the war. Attacking through the thinly held Ardennes region, the Germans hoped to cross the Meuse River and capture Antwerp, thus splitting the American and British forces in order to force a separate peace so the German Army could turn around and hold off the oncoming Red Army.

The Germans anticipated a rapid advance through the Ardennes as they had experienced in their 1940 invasion of France, but a combination of terrain, logistical issues, and stiff American resistance delayed their advance. This delay allowed the Allies time to divert forces to defend against the German offensive. On 17 December, the 101st Airborne Division received ordered to mobilize and the next day, the Division traveled over 100 miles in open-air trucks to secure the critical crossroads town of Bastogne.

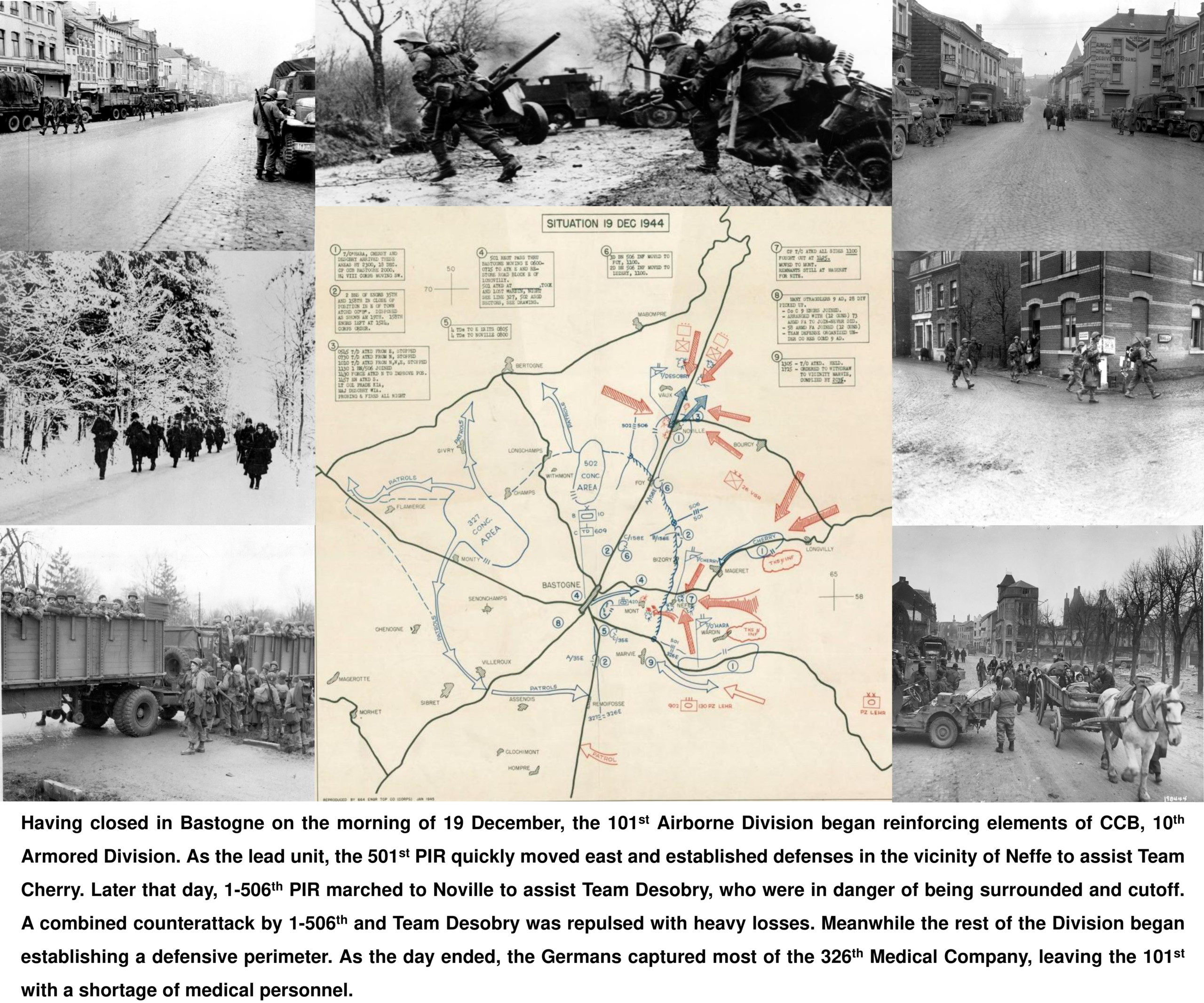

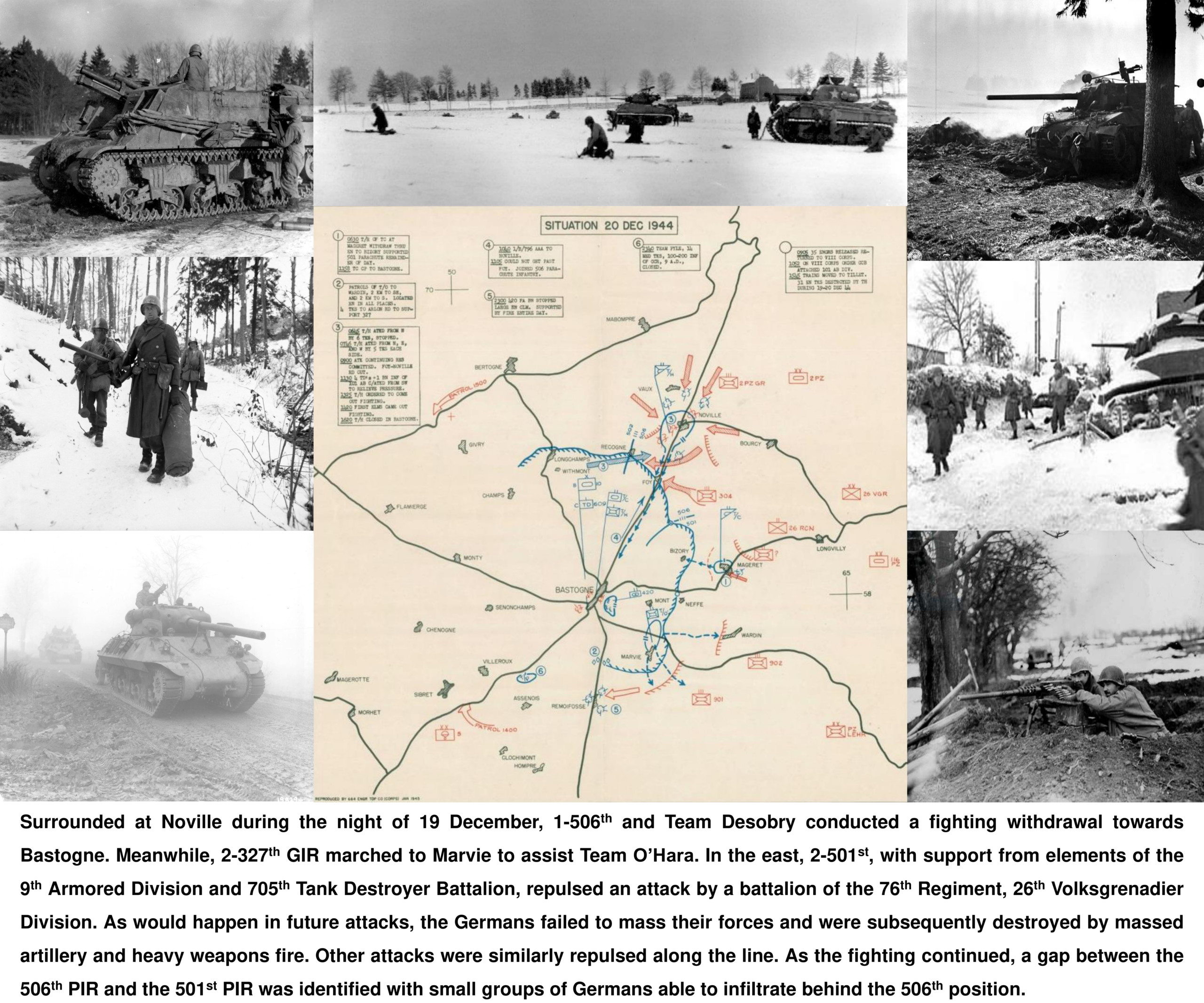

The German delay came at a heavy price for the U.S. Army. Units such as CCB, 10th Armored Division held the Germans off long enough for the leading elements of the 101st Airborne Division to arrive in Bastogne a mere four hours ahead of the leading German forces. The Division began establishing a perimeter around the town with the expectation that they would be surrounded. As the perimeter was consolidated, elements of the 9th and 10th Armored Divisions along with the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion were formed into a mobile reserve.

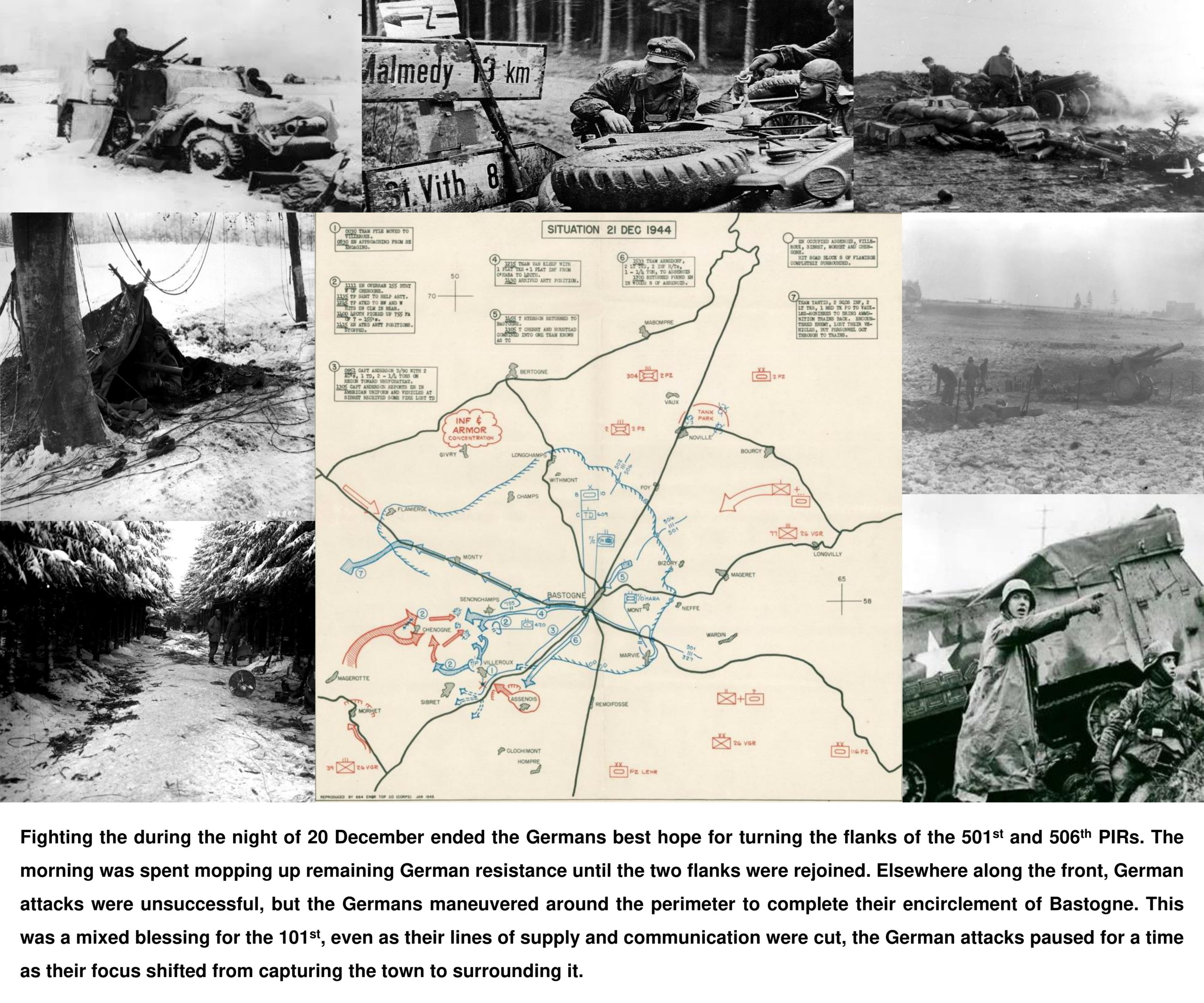

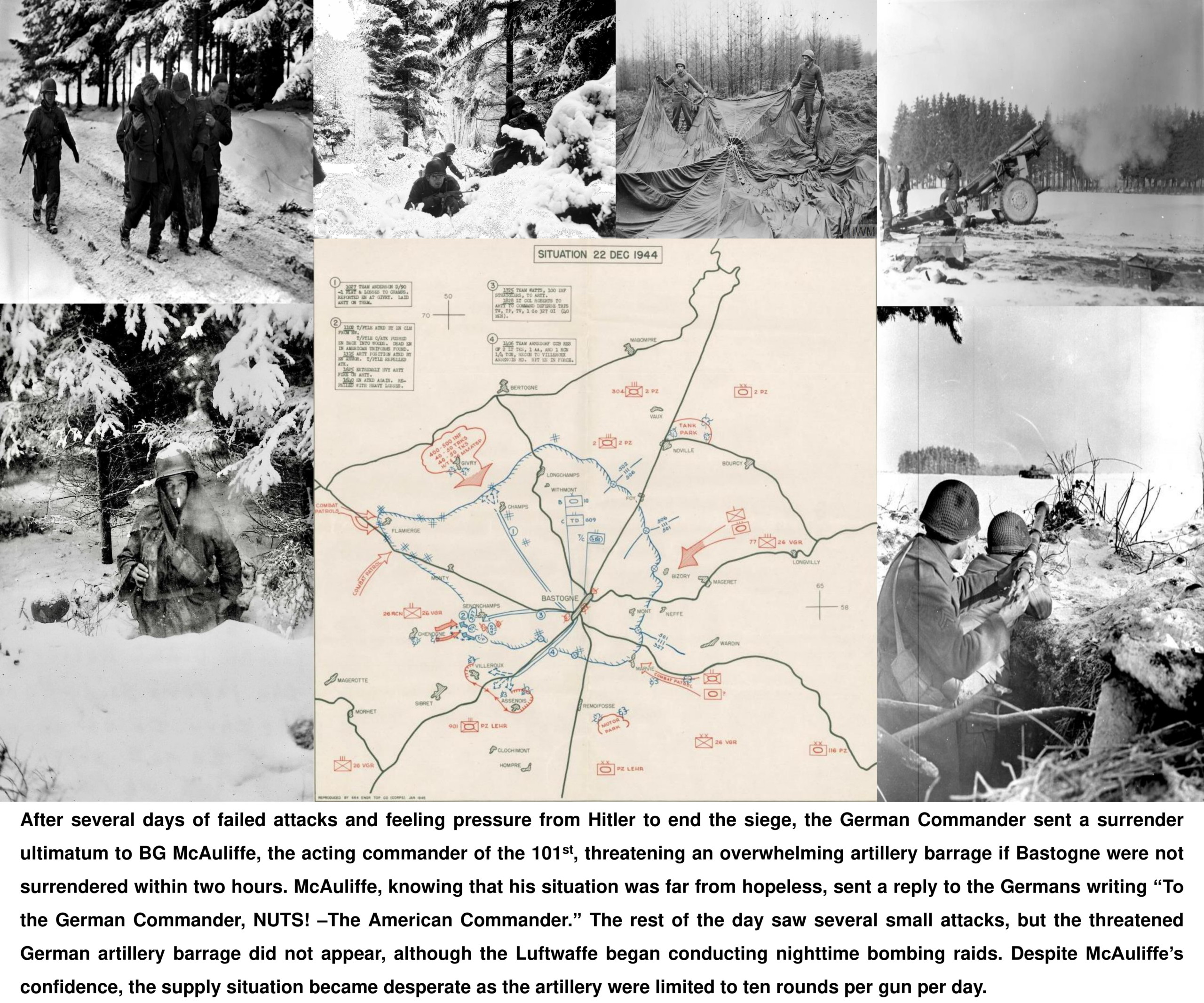

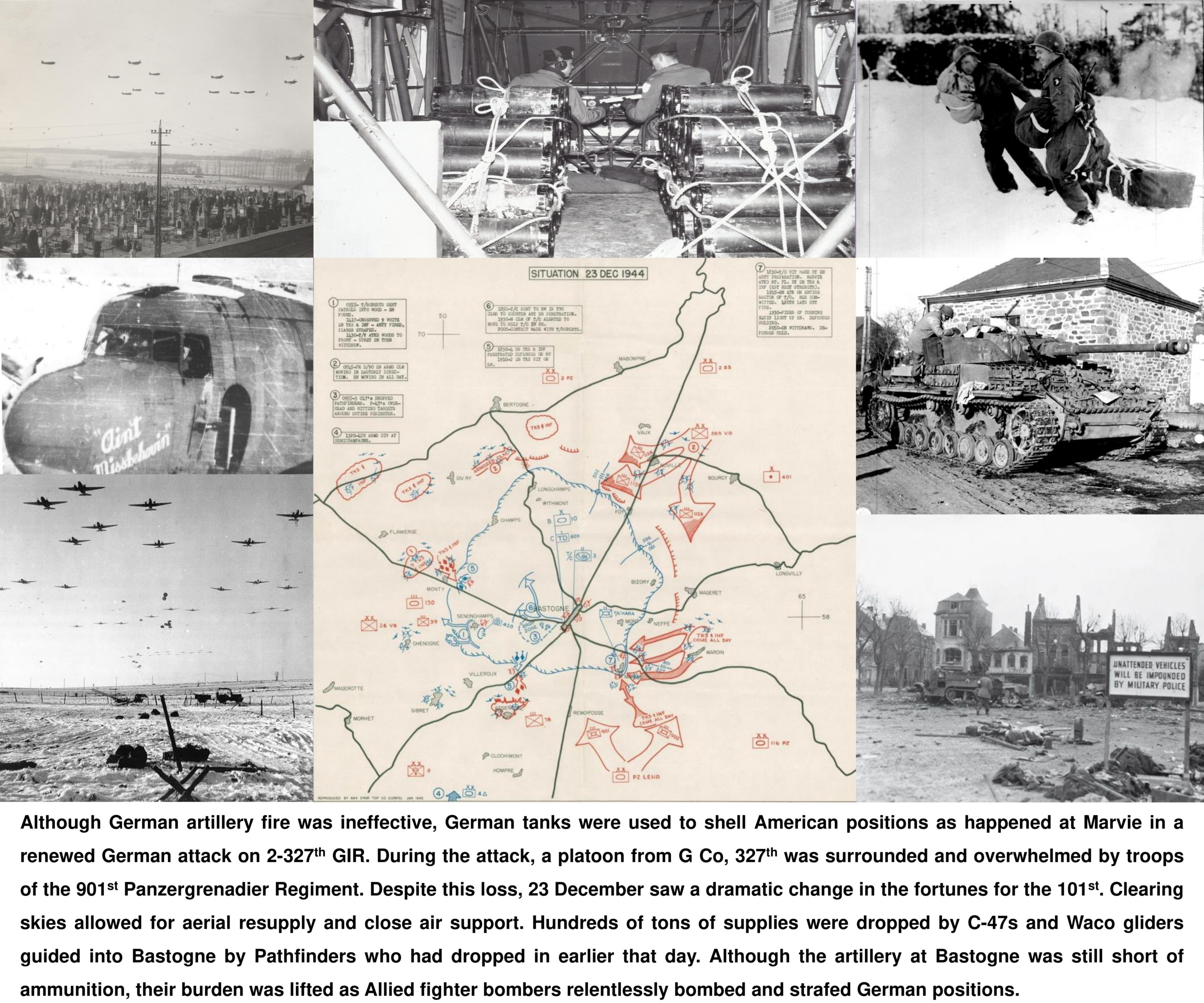

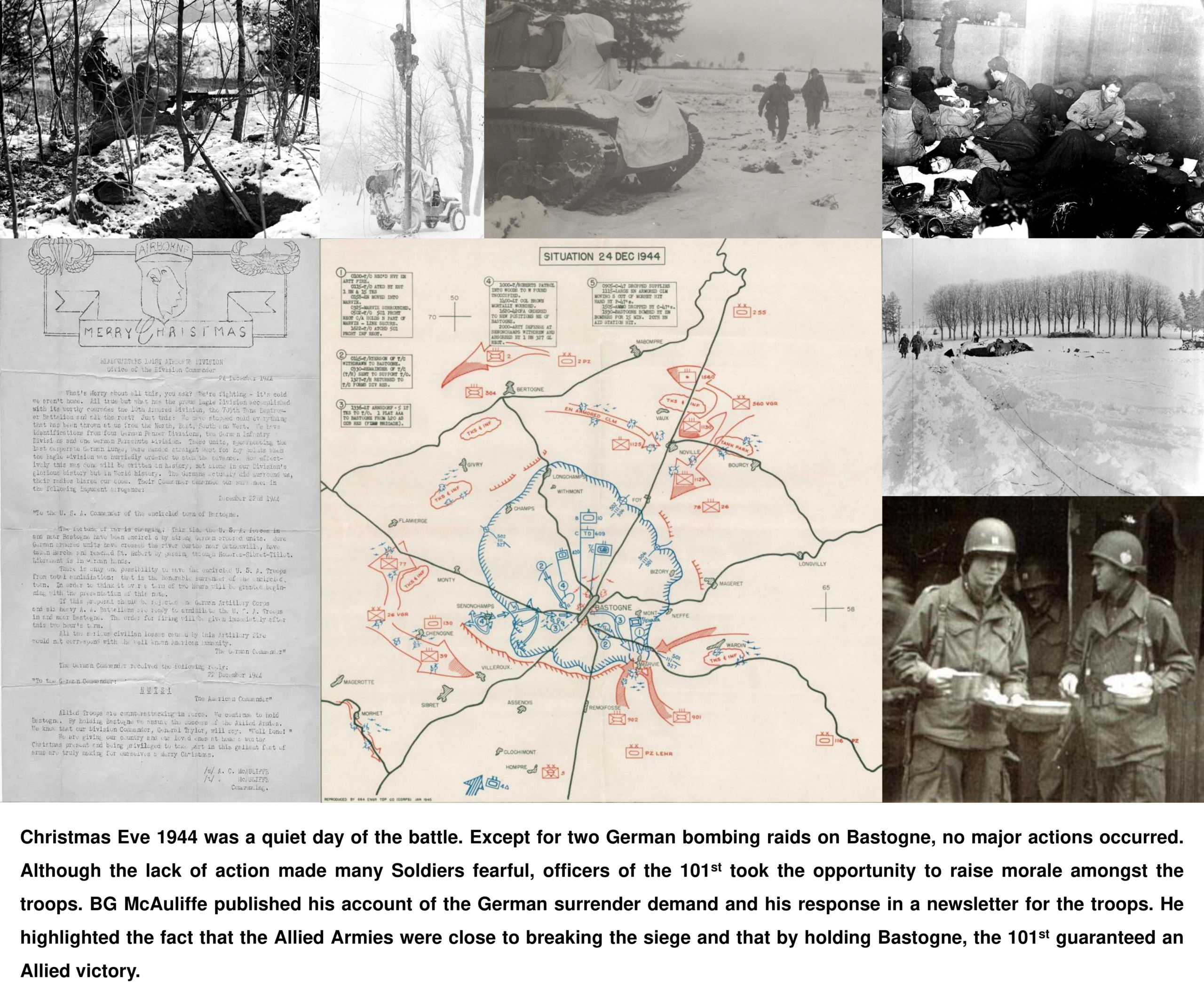

Over the next few days, the Germans launched repeated assaults against the Bastogne perimeter, but did not coordinate their assaults to occur simultaneously. This allowed the 101st Airborne Division’s Artillery to mass their fires and defeat the Germans attacks in detail. In desperation, the Germans sent a surrender ultimatum to BG McAuliffe, the acting commander of the 101st, on 22 December. Knowing the strength of his position, the quality of his men, and the likelihood of resupply, BG McAuliffe gave a short reply to the German ultimatum “To the German Commander, NUTS! -The American Commander.”

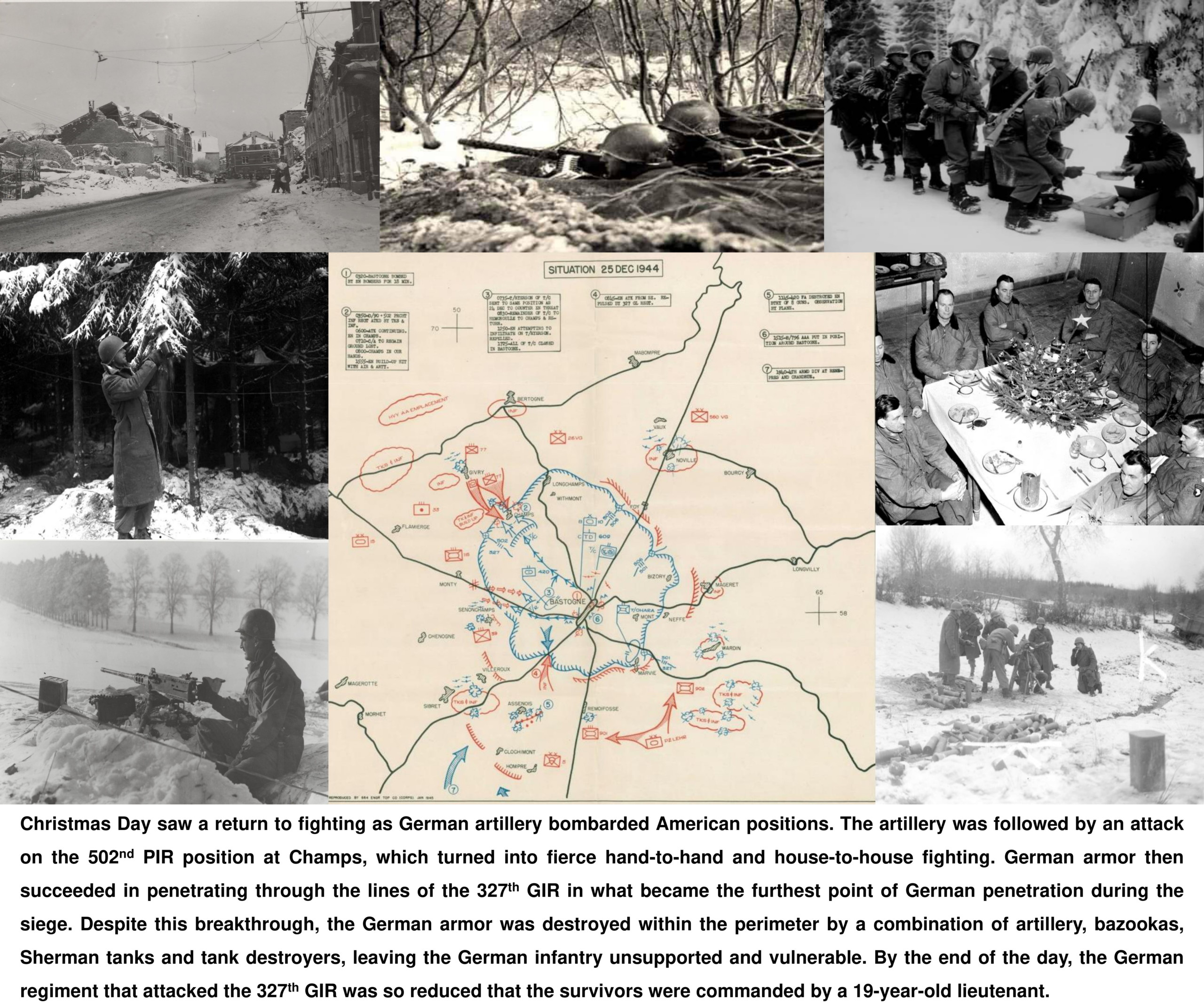

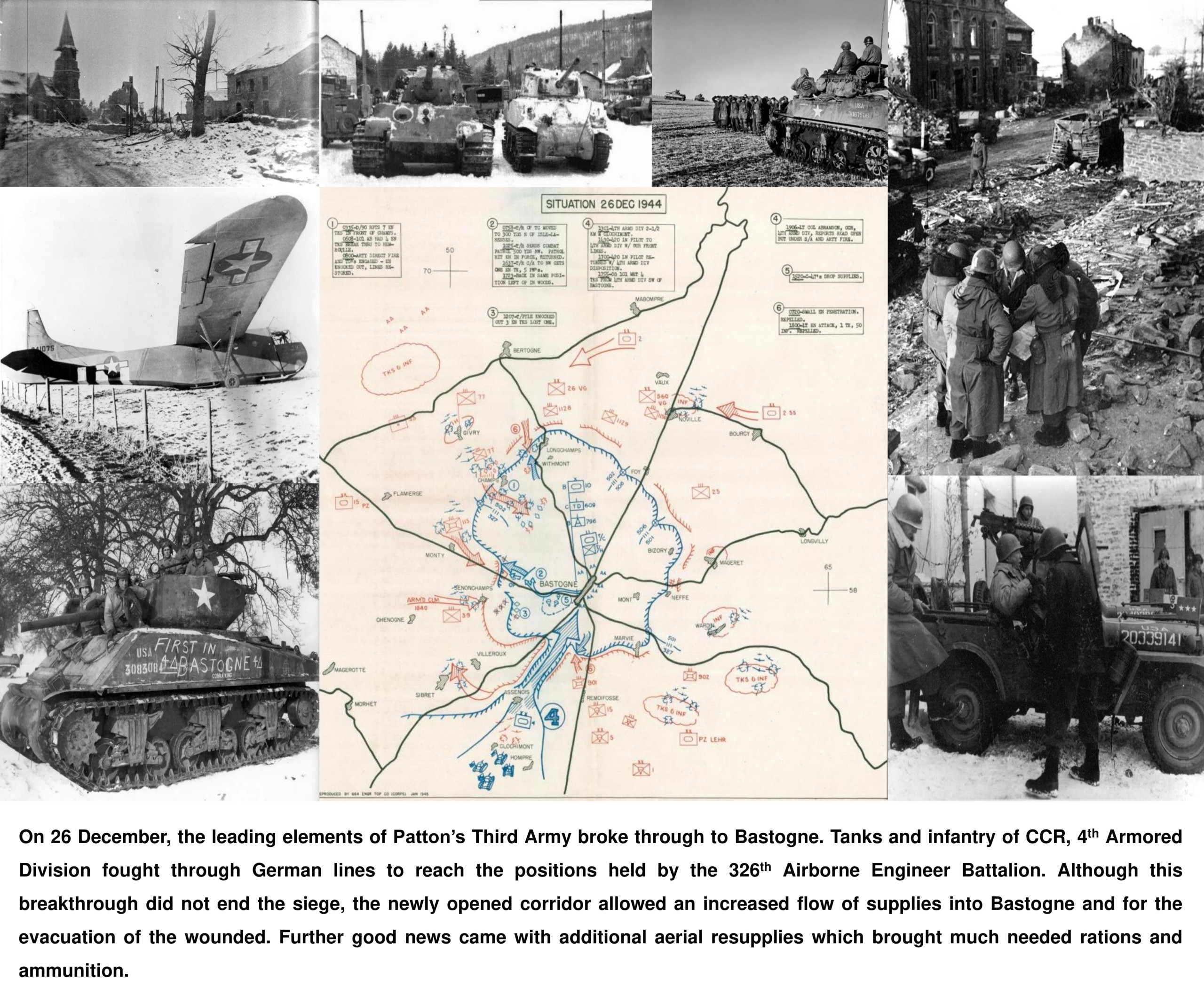

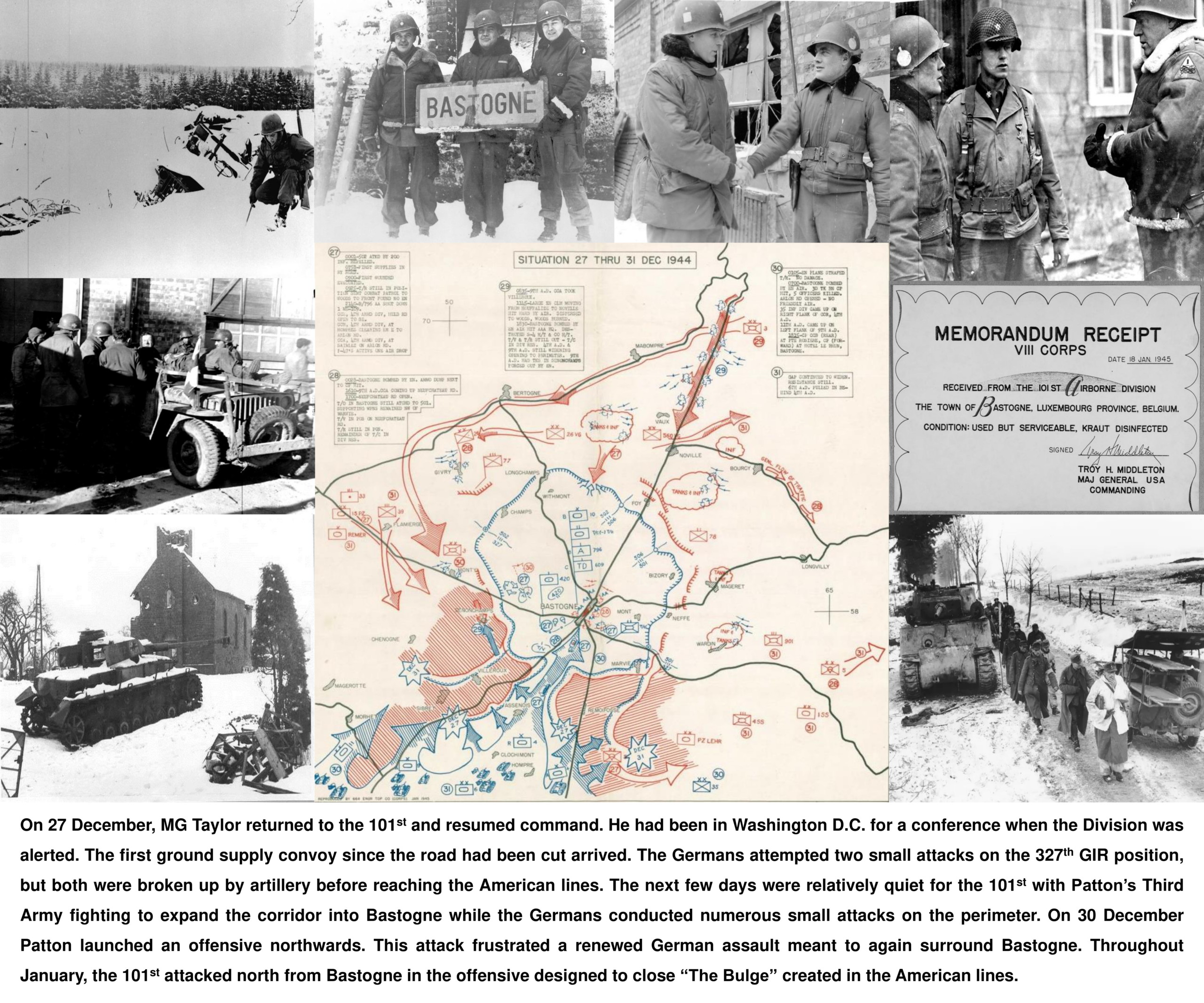

Despite McAuliffe’s confidence, the situation in Bastogne was becoming critical as the supply of ammunition, food, and medical supplies was desperately low as the Germans had cutoff resupply by road and the weather had not permitted an aerial resupply. The next day, the situation improved as the weather cleared, allowing aerial resupply and close air support to assist the Screaming Eagles. Further relief came when on 26 December, leading elements of Patton’s Third Army made contact with the 101st. With the encirclement broken, the 101st quickly began receiving resupply by both ground and air and the wounded could be evacuated.

While the 101st was not longer surrounded, the battle was not over. For the next few weeks, the 101st participated in the offensive to push the Germans back. The Division captured multiple villages it had been forced to abandon early in the siege such as Foy and Noville. Over the course of the campaign the 101st suffered 482 KIA, 2449 WIA, and 527 MIA/POW. Although it was later claimed that Patton’s Third Army rescued the 101st, no member of the Division has ever admitted to needing rescuing. The tenacity and resolve of the 101st in their defense of Bastogne frustrated the German plans and helped prevent the Germans from reaching their objectives.

~ Big thank you to our Division Historian, Patrick Seeling, for writing up this wonderful summary of the Siege of Bastogne!